Reclaim India’s pride through the science of ritualism

Sripuranthan is your average Indian village in Tamil Nadu. Short thatched houses, lush green fields, street vendors and roadside eateries. But residents said the village lacked its soul. The main deity from the village temple, an age-old Nataraja was stolen, smuggled and sold. The glue that held the village together was lost.

Fast forward to 2014. The Australian government returned the Nataraja to India; and it was brought back to the temple (albeit for a short while). This small town got its zeal back. The homecoming of their Devata filled a deep void felt by its community for all these years. The temple sprang back to life and the community was vibrant again.

Human beings have thrived in structures, stories and archetypes that bind communities together. Structures consist of different memeplexes shared by a set of people. In these memeplexes, faith or religion (for a lack of a better word in English) has probably been the most powerful and stable one. Religion in the Indian context is essentially a shared set of ideas, beliefs and rituals surrounding them. In India, rituals have played a very vital role in keeping our collective civilisational identity alive. Rituals are scoffed upon and laughed at a lot of times and rightfully so. But are all rituals equally bad?

SCIENTIFIC BASIS TO AGE-OLD RITUALS

Over the last few years social scientists have conducted in-depth research into analysing the value of rituals. Think about this scenario, you are about to go on the stage and address a large audience. You try to calm your nerves by indulging in some type of activity to take your mind off the immense task up ahead. It could involve an inane task such as tapping your feet on the ground, or taking a deep breath, or momentarily shutting your eyes. There may not be a purely scientific basis for the ritual you choose; but that doesn’t make it less important.

Rituals are like a set of repetitive actions (sometimes not even repetitive) that are conducted by humans in different settings. Rituals can be of a variety of forms, it could be in the form of prayers in the temple or some sort of physical activities that are performed before entering a job interview or a sporting competition. Looked at from an evolutionary lens, the sole purpose of a ritual is basically reducing anxiety to boost confidence, alleviation of grief during the loss of a loved one, or to perform better in tense situations like a sporting event.

Research seems to suggest that rituals can enhance the output of sportsmen. Any kind of a pre-performance routine performed before a game helps in a boost of confidence and focus of the individual who is about to go and perform in the sporting arena. Rituals seem to have a great soothing effect on humans. As per the work of Bronislaw Malinowski, observed in the practices of fishermen in the South Pacific Ocean. Safety and protection rituals would be a regular feature before fishing in turbulent shark-infested waters while none when fishing in calm waters.

A study in Brazil discovered that rituals help in solving problems like smoking and asthma. One could argue that there is an absence of a direct relation between ritual and the desired outcome, but what cannot be denied is that the performance of rituals i.e. repetitive actions, does have the power of effectuation in individuals. If you think ritualism is restricted to conservatives or traditional, then I invite you to the example of the most progressive festival in the world—Burning Man.

WHEN PROGRESSIVES EMBRACE RITUALS

Thousands of people gather and camp in desert in Nevada, and involve themselves in a wide range of “activities”. The event ends with a giant massive structure of the “Burning Man” being set ablaze. Every year, post the event, the organisers release an “Afterburn Report”, which gives the demographics of the attendees of the festival. Nearly 40% of the attendees are atheists and agnostics. And here you thought ritualism was a “religion” thing.

The latest Pew Poll suggests that religiously unaffiliated Americans (i.e. atheist, agnostic & unaffiliated) are equally likely as Christians, to hold New Age beliefs.

To summarise:

- The power in rituals is real.

- This power is compounded in shared, community-rituals.

- Many people who do not believe in religion, believe in rituals.

- Ritualism is a human-behaviour (not just restricted to religious belief-systems).

What opportunity does this present from a statesman or public-policy point of view?

Replace the Burning Man with Ravana and a few hundred Americans with millions of Indians celebrating Ram Lila. Multiply this by hundreds of rituals/festivals, across thousands of villages in India. The force-multiplier is infinite.

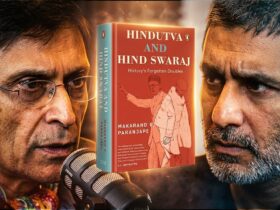

When I first came across the India Pride Project (and their very successful efforts to bring back India’s stolen heritage) it seemed like a purely cultural initiative. Over time, engaging with its founder, I have come to realise its multi-dimensional potential to quite literally stitch back the tears in our civilisation fabric.

This is precisely why we need to bring all our cultural antiquities and heritage back. A single Nataraja murti in Sripuranthan changed the mental make-up of that small town/village. Imagine the positive effect one can achieve societally if we brought back all the 200 murtis that the American government offered India in 2016. “Bring Our Gods Home” as a clarion call, is sound. Not just culturally, but scientifically. It can play a significant role in lifting the spirits of a society that could do with a bit of healing; especially considering the pain our netas cause us on a daily basis.

(This article was originally published on SundayGuardianLive.com)

Connect With Me