Universal Objective Moral Pluralism: Why the world needs it

Imagine this scenario, as you sit in the comfort of your house reading this essay on your cell phone or a computer there is a boy in some cases as young as nine being forced to dress as women and to dance seductively for an audience of older men. I am talking about Bacha Bazi, a tradition in Afghanistan where rich Afghans, usually across southern and eastern Afghanistan’s rural Pashtun heartland, or within ethnic Tajiks across the northern countryside, “buy” young men or boys for their entertainment.

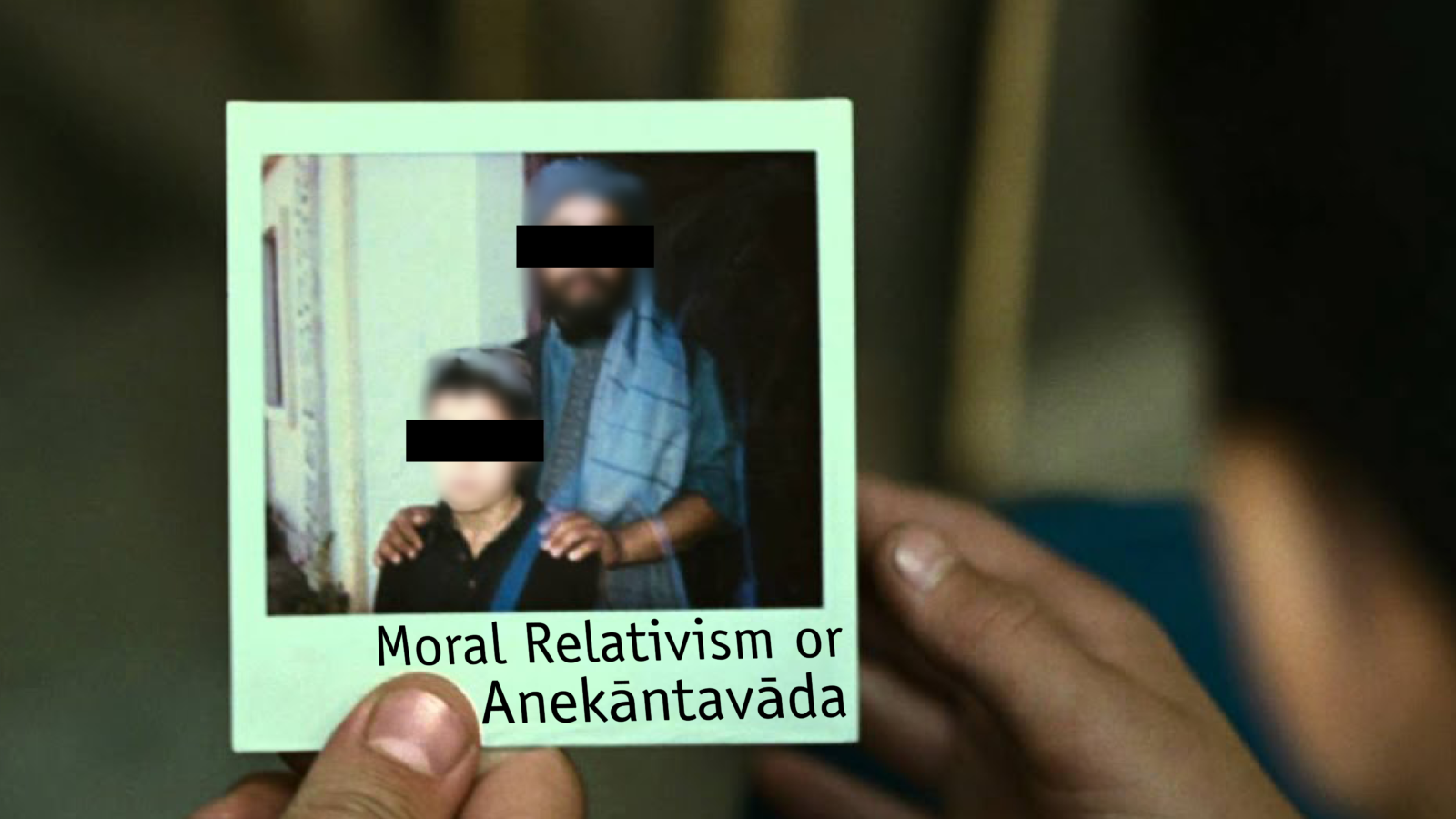

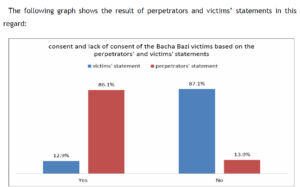

As per the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC) report “around 87 percent of these victims have stated that they have exploited them without their consent.”

So the question I want to ask everyone is Bacha Bazi right or wrong? Is this “cultural practice” good or bad? In other words is a practice where boys as young as nine years old are made to sleep with men, sexually exploited, made to dance, entertain adults Bachabazi parties and gatherings, serve as a servant at parties and gatherings where elder men touch their body organs, forcing them to massage bodies of the perpetrators, etc fine?

Lance Cpl. Gregory Buckley Jr. definitely thought this practice was abhorrent when he told his father “he could hear Afghan police officers sexually abusing boys they had brought to the base.”Special Forces commander Dan Quinn was relieved of his command “after he beat up an American-backed militia commander for keeping a boy chained to his bed as a sex slave.”

So were Lance Cpl. Gregory Buckley Jr and Special Forces commander Dan Quinn right for feeling absolutely gutted as they saw young boys being exploited? Or was it just another White Western Protestant Christian American imposing his worldview on another culture and multiple media outlets across the world then generating Atrocity Literature writing articles about it?

This leads us to the larger question; can we ever formulate a Universal Moral Code? Is there any such thing as a Universal Good and a Universal Bad? Can we ever come up with scenarios cutting across the entire human race where we can comfortably say that this value practiced by person A or sect B is wrong no matter how we look at it?

Before we delve any further let us first give a few definitions. We shall rely on The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Moral Relativism and Subjectivism: Moral relativism is the view that moral judgments, beliefs about right and wrong, good and bad, not only vary greatly across time and contexts but that their correctness is dependent on or relative to individual or cultural perspectives and frameworks. Moral subjectivism is the view that moral judgments are judgments about contingent and variable features of our moral sensibilities. For the subjectivist, to say that abortion is wrong is to say something like, “I disapprove of abortion”, or “Around here, we disapprove of abortion”. Once the content of the subjectivist’s claim is made explicit, the truth or acceptability of a subjectivist moral judgment is no longer a relative matter. Moral relativism proper, on the other hand, is the claim that facts about right and wrong vary with and are dependent on social and cultural background. Understood in this way, moral relativism could be seen as a sub-division of cultural relativism. Values may also be relativized to frameworks of assessment, independent of specific cultures or social settings.

Moral Objectivism: Moral Objectivism maintains that moral judgments are ordinarily true or false in an absolute or universal sense, that some of them are true, and that people sometimes are justified in accepting true moral judgments (and rejecting false ones) on the basis of the evidence available to any reasonable and well-informed person.

Another good definition is given by Mitchell Silver where he says moral objectivism is a process where a single set of principles determines the permissibility of any action and the correctness of any judgment regarding an action’s permissibility.

So what is the similarity between Moral Relativism and Moral Subjectivism?

Both frameworks claim/believe that there is no universal or objective moral standard and nor can we ever attain such a definitive position. So in short, in comparison to Moral Objectivism, both Moral Relativism and Subjectivism are at the opposing end. The only difference between the latter would be that Relativism claims that knowledge or morality exists in relation to culture or society and Subjectivism claims that morality or its knowledge is literally subjective to each and every individual.

In such a scenario one can defend the practice of Bacha Bazi. A Moral Relativist can use the framework of M. J. Herskovits where he says “Judgments are based on experience, and experience is interpreted by each individual in terms of his own enculturation”. It is because of that that we find the practice of Bacha Bazi morally repulsive because we are conditioned by our cultural norms that think harming young children is bad or wrong?

A Moral Subjectivist can say while they might find the practice of Bacha Bazi personally wrong, it cannot be universally wrong because morality directly stems from individual subjective experiences, and hence if an Afghani thinks Bacha Bazi is good they are justified in their individual belief.

Let us expand a little bit more on Meta-Ethics now. To understand this even better one needs to understand what Mitchell Silver calls Categorical Permissibility Rules. Silver says “without stirring from our armchairs, we can safely say that people are sometimes motivated by rules that they have accepted, such as ‘move chess bishops only along the diagonals’, or ‘floss daily’. Acceptance of a rule can, in part, constitute motives for actions. Not only can rules motivate actions, they also influence judgments about the correctness of actions. The rule about chess bishops underlies my judgment that it is incorrect to move a bishop along the horizontal. While there are no precise criteria for whether or not a person has accepted a rule, or for measuring the degree of acceptance, ‘acceptance’ implies that the rule has some motivational force and influence on judgments. It would be nonsensical to say, “Silver accepts the rule forbidding moving bishops horizontally, although he is not in the least inclined to follow the rule, nor does he see anything at all incorrect about moving bishops horizontally. Among the rules that can motivate actions and determine judgments are those that classify all possible actions as either permissible or impermissible.”

Now Silver himself admits that “a permissibility rule can be complex, and its application sensitive to circumstances. A permissibility rule may require that the time, place, effects, and the nature of the people involved be considered when evaluating an action. It may even take into account the acceptance of different permissibility rules by other people.”

But that does not mean we cannot have any working framework. Silver says “For instance, I know that there are people who categorically accept the rule that one should never mistreat their holy scriptures. I accept no such rule, but my awareness of others’ acceptance of the rule, combined with a rule I do accept, that everyone should show respect for others’ feelings, results in me not mistreating others’ holy scriptures. I do not respect the ‘holy scripture rule’ in itself; but I respect the holders of that rule, and in doing so I must often respect their rule. But this derivative respect for their permissibility rules does not mean I accept their rules to make my moral judgments.”

People often confuse differences emerging out of permissibility rules to mean that there can be no such thing as a Universal Moral Standard at all. Let us consider a case where we are morally dumbfounded. Jonathan Haidt explains this beautifully in his book The Righteous Mind where he shares this example “Julie and Mark, who are sister and brother, are traveling together in France. They are both on summer vacation from college. One night they are staying alone in a cabin near the beach. They decide that it would be interesting and fun if they tried making love. At the very least it would be a new experience for each of them. Julie is already taking birth control pills, but Mark uses a condom too, just to be safe. They both enjoy it, but they decide not to do it again. They keep that night as a special secret between them, which makes them feel even closer to each other. So what do you think about this? Was it wrong for them to have sex?.”

Now what Haidt says is that most people find this story to be morally repulsive even though they cannot rationalize their position as to why it is problematic on the face of it. Haidt says “morality binds and blinds”. He tells us that “We are products of multilevel selection, which turned us into Homo duplex. We are selfish and we are groupish. We are 90 percent chimp and 10 percent bee.” and “religion played a crucial role in our evolutionary history—our religious minds coevolved with our religious practices to create ever-larger moral communities, particularly after the advent of agriculture.”

Now that we have understood a little bit of Meta-Ethics let us ask ourselves this question that can there be something like The Worst Possible Misery for Everyone? Sam Harris in his book The Moral Landscape talks about this in some detail. He says “Even if each conscious being has a unique nadir on the moral landscape, we can still conceive of a state of the universe in which everyone suffers as much as he or she (or it) possibly can. If you think we cannot say this would be “bad,” then I don’t know what you could mean by the word “bad” (and I don’t think you know what you mean by it either). Once we conceive of “the worst possible misery for everyone,” then we can talk about taking incremental steps toward this abyss: What could it mean for life on earth to get worse for all human beings simultaneously? Notice that this need have nothing to do with people enforcing their culturally conditioned moral precepts. Perhaps a neurotoxic dust could fall to earth from space and make everyone extremely uncomfortable. All we need imagine is a scenario in which everyone loses a little, or a lot, without there being compensatory gains (i.e., no one learns any important lessons, no one profits from others’ losses, etc.). It seems uncontroversial to say that a change that leaves everyone worse off, by any rational standard, can be reasonably called “bad,” if this word is to have any meaning at all. We simply must stand somewhere. I am arguing that, in the moral sphere, it is safe to begin with the premise that it is good to avoid behaving in such a way as to produce the worst possible misery for everyone. I am not claiming that most of us personally care about the experience of all conscious beings; I am saying that a universe in which all conscious beings suffer the worst possible misery is worse than a universe in which they experience well-being. This is all we need to speak about “moral truth” in the context of science. Once we admit that the extremes of absolute misery and absolute flourishing—whatever these states amount to for each particular being in the end—are different and dependent on facts about the universe, then we have admitted that there are right and wrong answers to questions of morality.”

What happens when we use this framework and look at Bacha Bazi? Should we or should we not work towards creating a Universal Moral Code that abhors the specific practice of Bacha Bazi? The answer should be an unequivocal yes. Sam Harris is right when he says there is something like The Worst Possible Misery for Everyone. It does not matter which part of the world a child is born in. No child should be subjected to this horrendous practice.

Just because we do not have good enough answers in every single case does not mean that there are no good answers at all. In Evolutionary Psychology there are proximate explanations and ultimate explanations. A proximate explanation would be the one which focuses on the immediate causes of behaviour and an ultimate explanation would be the one that focuses on the effects for which that particular behaviour was selected. One could take a cue from Evolutionary Psychology and try to expand that worldview in the realm of Morality and Ethics. So while there might be proximate differences in our morals there has to be some ultimate moral code.

Also, one does not need to become an Abrahamic Moral Absolutist to understand that there is something like a Universal Moral Standard. In fact, one should fight that urge to become a Moral Absolutist and replace it with a Universal Objective Moral Pluralism. The answer lies in the Jain Framework of Anekāntavāda. The beauty of Anekāntavāda or “non-one-sidedness” / “many-sidedness” is that it does not promote a theory of relativism or subjectivism. In its quest to know the Satya or truth it creates an extremely flexible and plural “conditional yes or conditional approval” of any proposition by applying the epistemology of saptibhaṅgīnaya. The sevenfold path goes somewhat like this:

Affirmation: syād-asti—in some ways, it is,

Denial: syān-nāsti—in some ways, it is not,

Joint but successive affirmation and denial: syād-asti-nāsti—in some ways, it is, and it is not,

Joint and simultaneous affirmation and denial: —in some ways, it is, and it is indescribable,

Joint and simultaneous affirmation and denial: —in some ways, it is not, and it is indescribable,

Joint and simultaneous affirmation and denial: —in some ways, it is, it is not, and it is indescribable,

Joint and simultaneous affirmation and denial: —in some ways, it is indescribable.

So as it was mentioned a little earlier in the essay, Anekāntavāda in its own way recognizes that sometimes there are no good/universal answers to particular situations/questions in the realm of morality, metaphysics, or otherwise, but, it does not mean that there are no good answers at all.

If we were to adopt this flexible yet objective approach of saptibhaṅgīnaya one can easily find answers to multiple moral issues like Slavery, Racism, Birth Based Jati Varna, etc. We don’t need to say that slavery might be bad according to me but good for someone. We do not need to spin yarns of apologia around Jati-Varna and its fallout by saying that we first need to conduct ‘epistemological decolonisation’. Until we do not do that we cannot judge their results, and if we do any honest analysis today we are Western Modern Christian Protestant Reformists.

When someone tries to morally judge Jati Varna (hereditary social structures) we do not need to give disclaimers on whether we have been burdened with Western Christian Ethnocentrism. We do not need to make excuses and say that we have been unfairly overburdened because of the West and their newfound guilt complex around race. We can admit without any ifs or buts that yes discrimination has emanated out of Birth Based Jati Varna, and this practice is morally wrong and we need to reject it lock stock and barrel.

Isaac Asimov had once said, “Never let your sense of morals prevent you from doing what is right”. So let us all work together in building a Universal Moral Plural Framework which will lead to more and more flourishing of our planet and all the species that are part of it.

Connect With Me